By Eleanor Abraham

‘How do you extract text from a PDF?’

This is a question I see posed quite regularly in writers’ forums – and sometimes in editors’ forums too.

There are a couple of ways to convert a PDF into a text file, but I’m not going to tell you about them.

Am I some kind of jerk? Quite possibly, however, that is not immediately relevant to the original question. In response to the first question I would ask another question (definitely a jerk): ‘Why do you want to?’

Panic

A quite common answer is that a writer has just had their book formatted but they have spotted the breed of typo that only reveals itself after paying for typesetting. The writer panics. For whatever reason, they think that, rather than asking their typesetter to make the changes, it might be necessary/better/cheaper/less embarrassing to make the changes themselves. Maybe they will even find some magic workaround (that two dozen internet-forum publishing experts will be only too glad to tell them about).

But this is not a good option.

The simplest solution

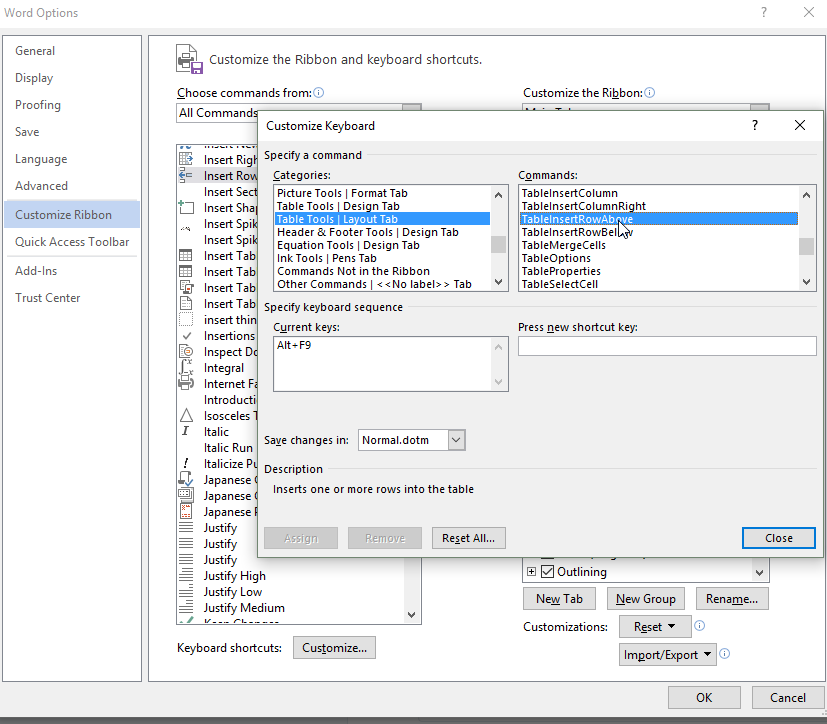

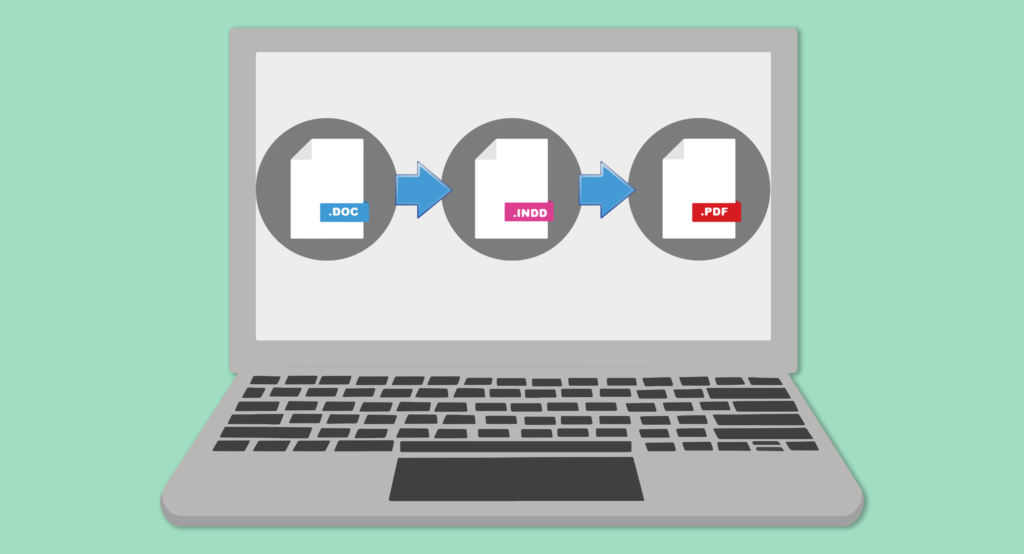

The simplest solution – even if it’s potentially a bit awkward, given that they told the typesetter the book was the (last, final-final, very correct, no mistakes, yes I hired a proofreader, definitely) final draft – is to ask the typesetter to make the changes in InDesign and export the PDF again. (InDesign is the desktop publishing software that the majority of typesetters in the industry use to create book interiors.)

PDFs from publishers

In another scenario, an editor will be given a PDF to mark up. I’ve seen some editors panic and assume the client has made a mistake. (In the editors’ forum, three dozen other editors concur, saying ‘Editing must be done in Word alone – so mote it be!’)

But a publisher client is unlikely to thank you for returning a marked-up Word file when they wanted a marked-up PDF.

It is now possible to import PDF comments into an InDesign file. It’s a great feature that means that any last-stage layout correction is quicker and easier to do.

So, changing the format of the file from a PDF to a Word document might create a lot of work for your publisher client.

Good communication and understanding the brief are key. I also think that knowledge of a project’s workflow allows you to appreciate why you’d be better doing things in a certain way.

Editing PDFs

Another common question is: ‘Can you edit a PDF?’

Yes (four dozen people in the editors’ forum will tell you) it is possible to change the text of a PDF.

But just because it’s possible doesn’t mean you should do it.

To be clear, I’m not talking about using the comment and stamp tools in Acrobat Reader, but using the text editing tools that are available in Acrobat Pro.

Imagine the scenario we mentioned above of a self-publisher who has realised their beautifully designed book interior did actually need a proofread after all. The client contacts an editor to ask them to correct their gorgeous mistake-ridden text directly in the PDF.

Do not be tempted to do that.

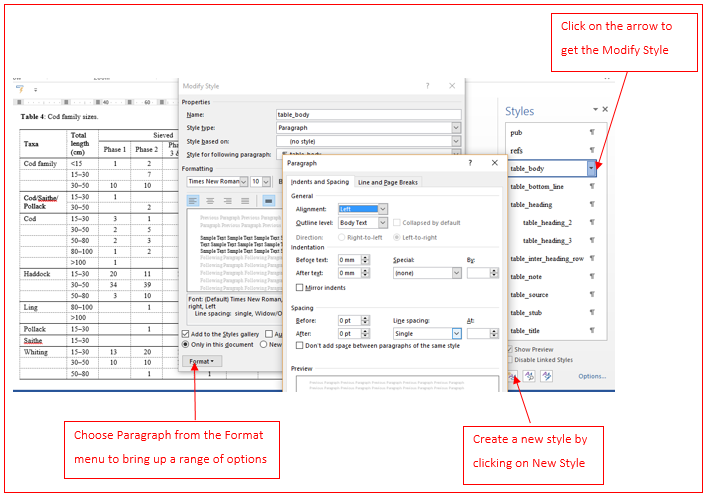

In this instance, we really need to contact the typesetter to get them to do the corrections in InDesign. Or, if the book’s mistakes are extensive, ask the typesetter to export the text from InDesign into Word again so that it can be proofread. They can do this in a way that retains all the paragraph and character styles, that can then (theoretically) be smoothly re-imported back into the InDesign layout.

File-version control

For reasons of file-version control, and to futureproof any later editions of a book, final text corrections need to be done in a master file, and by the end of the project that file will probably be the book’s InDesign layout. Changing the actual PDF means that if you come to update, publish in a new format, or repurpose the text, the last corrections won’t be in the very file that would have been the best source for the new edition. Doing the corrections in the PDF may create a problematic layout, with uneven lines or unjustified paragraphs. It might also mean fonts do not appear as they should. All this would have been easily avoided by using InDesign.

The secret’s out…

OK, I admit it, I proofread PDFs a lot, and I do extract text to Word. But I do it in order to run macros for consistency checks. If I find mistakes via the Word file I then mark them up in the PDF… because that is what the client wants.

TL;DR (Too long; didn’t read)

Can you extract text from a PDF in order to edit it? Yes, but just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eleanor Abraham has worked in book publishing for over 25 years, including (simultaneously) a stint in production journalism for about 10. She is an editor, typesetter, occasional writer, perpetual cat bore, and a CIEP Advanced Professional Member. Her specialist areas include commercial fiction, humour, computer science, Scottish interest, and – a sub-genre that is admittedly rare – the comedy cookbook.

You can follow Eleanor on Twitter

https://twitter.com/EBAeditorial

Pic credit: Montage uses pics courtesy of evrywheremedia and OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay.